A letter to my Canadian publisher about last night’s World Series game

First of all, no. No, games do not usually last that long. In fact, they never last that long. An 18-inning game is in fact two games. This is unprecedented — a word sadly overused in our beleaguered times — but it is. I am sure you didn’t stay up to watch. At 11:24 my time, you texted to me: “These innings take forever. I am not even watching, but it is hard to go to sleep when it is tied.” I was already asleep, and the ding on my phone woke me up. It is impossible to watch the game in the U.S. without a subscription to Fox Sports, and I do not have one, for various reasons.

Later in the night, I woke up. Not at three — “In a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning,” wrote F. Scott Fitzgerald — so say it was two o’clock in the morning, when I checked my phone (sleep experts say you should not do this, but perhaps this is why I am so very very tired) and the game was still tied.

“Nobody on, nobody out,” I mumbled to nobody. I rolled over and went back to sleep. Perhaps the empty room appreciated the literary reference to my long-unpublished novel, Nobody On, Nobody Out, my second novel, and the first novel for which I had a literary agent.

So my second novel was what should have been my first novel, an autobiographical coming-of-age. (Instead, my first novel, Cooder Cutlas, was a rock and roll on the Jersey Shore story, which I believe if I’m not mistaken is a story quite in vogue this week?). So, Nobody On, Nobody Out follows a weekend in the life of a teenaged girl in a motherless, baseball-obsessed family. Our heroine, Alison, an aspiring sportswriter, is playing Helena in her school’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream while also following the progress of her team, the St. Louis Browns, in the American League Championship Series playoffs. (The St. Louis Browns were a real team who moved to Baltimore in 1953 and became the Baltimore Orioles. Similarly, the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958. You do not need to know this, except that it is something that can be known.)

At the time, the American League had a rule that a game must end at midnight. Because of that, and various rain delays, the game in the novel lasts an entire weekend. I wrote this novel on a typewriter in my sister’s spare bedroom in Philadelphia and when it was finished I mailed the paper manuscript to an agent at the William Morris Agency who had expressed interest in my writing career. He did this by placing his hand on the manuscript for Cooder Cutlas and intoning, like a bailiff in a courtroom, “I think this is a good book.” (Dramatic pause.) “I don’t think this is the best book you will ever write.”

He said the same thing about Nobody On, Nobody Out, eerily predicting the long and thankless road my writing career would take. I did get an another agent for that novel, however, and over the course of a year gathered a soft, leafy pile of rejection letters, full of praise but ultimately rejecting the work as “too YA.” (This was well before YA became a desirable thing — it was still something of a publishing ghetto at the time.)

Nobody On, Nobody Out, anyway, Netta, was inspired by a 1974 game between the New York Mets and my beloved St. Louis Cardinals which lasted 25 innings and lasted seven hours and four minutes (don’t be impressed — I had to google this.) It set records in various ways. I did not stay up to listen to it; it was a school night. But my father did. Of course my father did. We were awakened from time to time by the sound of his hand slamming against the counter when a play did not go as he wished. This was the soundtrack to my childhood.

So no, Netta, games do not always go on that long. But yes, they are always that slow. When I say “slow,” I mean leisurely. This is why baseball is the preferred sport of poets. Baseball allows you time to think. Not the kick-kick-run-run of soccer (or “football”) or the war-game-meets-planning-committee bluster of American football. It is a strategic. It is a duel. It is bucolic, going back to agrarian roots.

“It is summer,” wrote William Carlos Williams. “It is the solstice/the crowd is/cheering, the crowd is laughing/in detail/permanently, seriously/without thought.”

Another poet, Robert Frost, wrote “Poets are like baseball pitchers. Both have their moments. The intervals are the tough things.”

The intervals are the tough things, don’t you think? We are in a tough interval as a national here down south, and I think those of us who are not enamored by the frenzy of other sports find solace in the leisurely pace. It reminds me of Jordan Baker’s line in The Great Gatsby: “I like large parties. They’re so intimate. At small parties there isn’t any privacy.” Similarly, baseball is intimate, and the busy sports don’t afford you any privacy, any time at all to spend with your thoughts.

And there is nothing more beautiful in the sporting world than Dodger Stadium as the sun goes down.

Saorsie the Shepherdess

Yesterday, I took the train north to begin a weeklong stay at the Hudson Valley Writers Residency. For my train reading, I brought along the book Learning to Look at Sculpture because I have been searching for a primer on sculpture in order to grow smarter for the Mark di Suvero sections of the dog café book. (I have decided on the title We Live in Hidden Cities, but its every day title is “the dog café book” or, as a texting friend typo-ed to me recently, “dog cage.”) I didn’t learn much about sculpture beyond “it is an art form with which we share space.” I fell into conversation with my Amtrak seatmate, a handsome young woman in the vein of Julia Stiles.

Readers are reminded that the description of this website contains the phrase “champion of the chance encounter.”

My seatmate was on the last leg of her trip home from Scotland, where she had gone on an Outlander tour. (“Lallybroch!” “The Battle of Culloden!”) I am fluent enough in Outlander (the show, not the books) and then we branched into various things Scottish. I told her that it is my ambition to do a residency at Hawthornden Castle outside Edinburgh, and that I was on my way to a residency for the week. What am I working on? The history of one block in my neighborhood. She told me that she was majoring in history and had recently written a paper about how women’s history, so often obscured from the written record, can often be found in textiles. She attends SUNY Empire, an online program, which enables her to help out on the family farm, further upstate, where her family raises livestock, mainly sheep.

It struck me that leaving a sheep farm to vacation in Scotland was something of a busman’s holiday. I didn’t say this to her because she is 20-something and I doubted that she would know the term.

Instead, I said, “So you’re a shepherdess.”

Her mother is writing an historical novel about the family farm. I am all for historical novels (having written one and having one in a state of benign abandonment) and read over the summer Ben Shattuck’s The History of Sound, which a poetry professor at MY SUNY program told us was a collection of short stories written in a form called hook-and-chain, a form popularized in New England in the 19th century, which follows the pattern a bb cc dd ee ff a. I recommended this book to the shepherdess, along with Andrea Barrett, who I recommend to everyone. She didn’t write any of this down – I was a stranger on a train bothering a young woman who’d flown to JFK from Scotland, then taken the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station to get an Amtrak to take her upstate to her farm. But maybe she will see this.

Champion of the chance encounter.

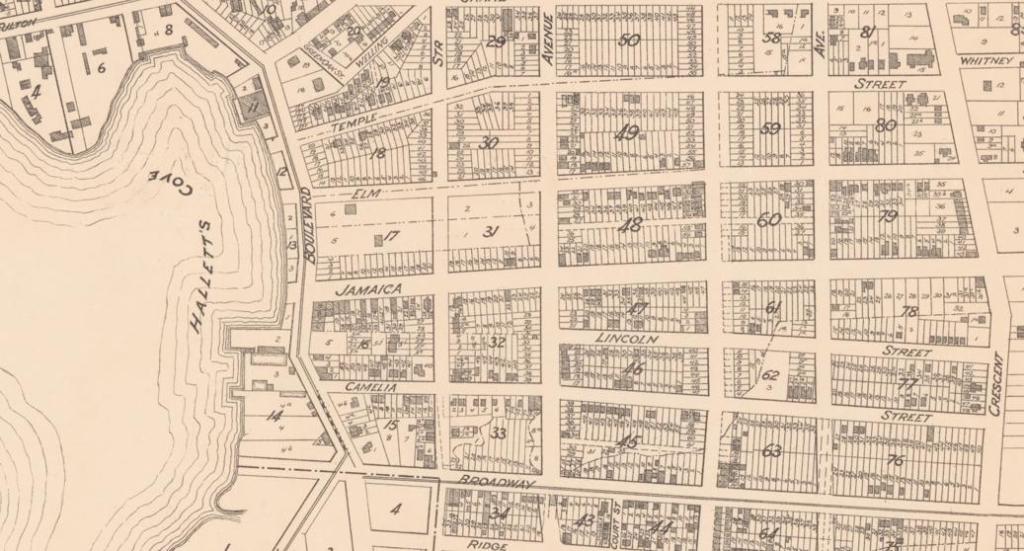

Earlier this summer, I visited the Queens Historical Society to see if I could get an answer to the question, “What was that parcel of land that juts into the East River between the time it was Stephen Halsey’s house and the time it was turned into NYCHA Housing?” I looked at maps and chatted with Jason Antos, the historian on site. Then since I was on the 7 line anyway, I took the 7 train to the Trader Joe’s in Long Island City, where I wound up chatting with the cashier as she checked me out. She too is a history student and had written a paper on the history of the Gowanus Canal. She later read this very blog and sent me a brief history of remonstrances, which I had been in search of, curious as to whether there was a precedent for the Flushing Remonstrance, or whether that particular set of early Long Islanders came up with the idea of writing a public letter to Peter Stuyvesant to protest his religious intolerance. (They did not come up with it. Remonstrances were a thing going back to King John of Magna Carta fame, according to the historian currently working the cash register at the Long Island City Trader Joe’s.)

Historians are everywhere, might be the moral of this post. Or, it pays to talk to strangers. Also to carry a business card.

Shzu Shzu

The café was a new one for me, so small it seemed I could hold it in the palm of my hand. It was called, fittingly enough, Café Sparrow. As I sat with my morning coffee and notebook, I was accompanied by the conversation between a man and a woman at a table an arm’s length away. Had I been at my usual café, I would have been overhearing a conversation in Greek. But I was one avenue and seven streets away from my usual spot and in Astoria, that distance takes you over a border into another country.

I suspected they were speaking Serbian. I’ve often thought that if cats developed the ability to speak like a human, the language they would choose would be Serbian. The rolled R’s and the shzu shzu consonants would prove so easy to navigate. As for the breakfasting couple, I loved the sound of their language. I would have asked them what it was. But I was afraid they would think I was from ICE.

Long ago in civics class, we were assigned to write a term paper on one of the federal agencies. (Nearly every part of that sentence is hopelessly quaint.) I chose, as it was then known, the Immigration and Naturalization Service – INS. One of the stated objectives of INS, created by FDR in 1933, was to “supervise the immigration process.” In 2003, as part of the Homeland Security Act, ICE was created – Immigration and Customs Enforcement. One of the stated objectives of ICE is to operate the “removal process.” For “naturalization,” (to become a citizen is to become “natural”), you must go to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. But you don’t hear much about USCIS, and perhaps I should not have mentioned it.

Some people fond hearing a language that is not English “uncomfortable.” I have in my time been made uncomfortable by language. When I was at CBS, my first job out of film school, my boss used to leer at me with his palm against my neck, “Oh, if I were ten years younger.” This made me uncomfortable. When my father, responding to my complaint about this behavior, replied, “Can’t you put up with it?” I was uncomfortable. When the HR assistant at ABC, shaking her head at my resume which included my degree, two years under siege at CBS, and a novel under contract from a prestigious publisher, told me “Only secretarial positions are available,” I was uncomfortable. (And skeptical.)

But that was language directed at me specifically, and I am using “language” here in the definition “choice of words” not “a system of communication used by a particular country or community.” Although I was made uncomfortable by the latter definition when I worked at an Italian law firm (having switched industries, feeling no love or money from television) and two people conversing in English in front of me, gave me the side-eye and switched to Italian. That behavior was deliberately exclusionary, as opposed to the Serbian couple at Café Sparrow, who were merely conversing.

I wanted to ask merely, “Hey, what language is that? It’s beautiful.” I remember asking a man in a wine store “Are you speaking Portuguese? Such a beautiful language.” I guess I’m not made uncomfortable by the sound of other languages. I guess I have no conclusion to offer that isn’t naïve or too hopeful or too bleak. I guess I am fond of the sound of purrs and shzu shzus.

Where the Streets Have No Name

My friend Lee once sent me a card that came back to her because she had misaddressed the envelope – nearly all the streets in Queens are numbered and many share a number, so that there is a 31st Avenue, Street, Road, and Drive within walking distance of me. All of the roadways once had names, of course, and they were all changed to a numbering system.

In 1898, Queens County decided to consolidate with Manhattan. While Brooklyn was an entire city when it joined Manhattan. Queens was a county of small villages, each with its own Broadway, its own Main, its own Elm.

A one-time official Queens Historian wrote: “By the 1920’s, in order to rationalize the maze of gridlets and ensure connectivity of the system, the Queens topographic bureau imposed an evenly spaced master grid over the entire borough. Streets began in the west in Long Island City and Avenues began in the north in Whitestone. . . named streets followed the contours of the land.”

That does not appease Lee, who still stings from the return of her greeting card. But it was Lee I thought of as I read through the minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Village of Astoria, 1839-1870 last week at the New York City Municipal Archives.

About a year ago, a man whom I don’t know and didn’t ask informed me on social media that the history of Astoria begins with Stephen Halsey. This unasked man is correct, I suppose. The history of the land does not begin with Halsey, but the history of Astoria does – it was incorporated by the New York state legislature in April 1839, and Halsey is the reason it is named Astoria. Halsey was a fur trader who was chummy with John Jacob Astor, which I suppose it was necessary to be if one was a fur trader at that time. But here I will defer to Rebecca Bratspies, a professor of environmental law at CUNY Law School and the author of Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues & Heroes Behind New York’s Place Names:

Stephen A. Halsey, founder of the Astoria neighborhood of New York, proposed naming the town after John Jacob Astor in the hopes that Astor would make a large donation to a young ladies’ seminary, which would also be named after him. Astor made the donation, but instead of the generous support Halsey had been hoping for, Astoria donated only $500 to the Astoria Institute . . . Astor himself never visited Astoria, even though he could see it from his country house on the other side of the East River.

Halsey is all over these early years, according to the minutes. I thought that minutes of a board of trustees would be dull reading, that I would be finished by lunch and on my way to the rest of my day off from the office. And they were dull reading – the building of walls, sidewalks, sewers, the maintenance of wells and pumps, the grading of streets, the placement of street lamps, the establishment of a fire department, the naming of a police constable. But they were also fascinating and kept me there until the archives closed, as I read the story of transformation from a bunch of farms and fledging factories being shaped into a town. Many of the early meetings were held in Halsey’s home.

And then I came upon the naming of the streets. Lee would rejoice!

“RESOLVED that a new street sixty feet wide to be designated as “Grand Street” shall be laid out and opened commencing at Welling Street and running in an easterly direction as far as the village limits extend along the line between the lands of C. B. Trafford and B R Stevens on one side and R M Blackwell – Buchanan & Gabriel Marc on the other side . . .”

Also established in these early minutes: Main Street, Flushing Avenue, Newtown Avenue, Sunswick Terrace, Greenock Street, Welling Street, Emerald Street, Linden Street, Woolsey Street and Remsen Street. Grand Avenue (not street) is now a subway stop, Remsen is 12th Street, Welling is Welling Court, Sunswick is a buried creek, and Newtown Avenue is Newtown Avenue. The rest would require some digging.

Certain prohibitions were also introduced: no person shall allow his livestock or fowl to wander at large, set off gunpowder or combustible material in public places, swim in the East River near the ferry slip or appear naked in a public place, or “raise or fly a kite in any street lane or alley within the village under the penalty of Five Dollars for every offence.”

I wondered what the deal was about flying a kite. There were no telephone lines to disrupt in 1848, and I doubt that there were all that many kites. I would have asked the friendly archivist, Marcia, but Marcia, who is from Flushing, had already hurried away to find a law dictionary when I asked her about the Flushing Remonstrance. I know about the Flushing Remonstrance; it was that word “remonstrance” that has bothered me. Were there other famous remonstrances?

There were remonstrances in the board of trustee minutes. A farmer remonstrated that the location of Grand Street would destroy some of his trees. The Hook and Ladder company remonstrated that the proposed Village Hall should not be in the firehouse.

More exciting to me than the evidence of other remonstrances was Marcia, the archivist, who responded to my questions with lots of information – files dug up, an Excel spreadsheet of other sources emailed to me, suggestions as to where other information might be housed. I hadn’t realized how parched I was for a sympathetic ear until she provided a gentle sprinkling of support. Writing is a lonely business at the best of time; writing researched nonfiction when one is not a journalist or historical can seem deranged.

“How’s your history of Astoria coming along?” smirked a work colleague at a recent lunch. Granted, this particular colleague can make the response to a mild “How are you?” sound scathing, but this dash of scorn reminded me to be careful who I tell (as my fellow writer but not relative Joan Frank once advised).

I know, I know. Be grateful for the librarians, the archivists, the other lonely historians, the kind stranger who gave me permission to quote from her PhD thesis on Mark di Suvero. Be grateful, and tell the naysayers (quietly, of course) to go fly a kite.

“Poetry makes nothing happen” . . . but poets laureate do

Last month, I sailed down the East River and across New York Harbor to attend the New York City Poetry Festival, which is held annually on Governor’s Island. This journey required two ferries. On the second ferry, I met Phylisha Villaneuva, an MFA candidate in poetry at St. Francis College, and the poet laureate of Westchester County. I asked her how she had obtained the position of poet laureate of Westchester County, and what the job entailed. The answers, in order, were: she applied, and the usual – a tenured appointment, a small stipend, the performance of readings, the teaching of workshops and a commitment to the enthusiastic promotion of poetry in the community whenever an opportunity arose.

I had no doubt Phylisha would fulfill these obligations. She could not contain her excitement about her upcoming reading at the festival, her MFA program, and the beauty of the very hot day, an enthusiasm which did not diminish even when we discovered that we had taken the wrong ferry to the island. Apparently, there are two ferries to Governor’s Island and the one we took, which leaves from Pier 11, what you might call the Grand Central Station of the ferry system, left us at the spot on the island that was possibly the further possible point from where the festival was taking place, which was near the other ferry, the one that leaves from the Staten Island Ferry terminal.

I was there to help man the table for Poets of Queens while they performed in their allotted time slot, but since I took the wrong ferry and wasted time roaming the island, lost, I arrived to an empty table. While poets from three competing stages orated in the distance, I unpacked the t-shirts (which you can find here) and the group’s most recent anthology (which you can find here).

I am not a poet of Queens. I am studying poetry and I live in Queens. But Poets of Queens, which is run by Olena Jennings, is a group that helped me make the transition from novelist of historical fiction about WWII Bermuda to flaneuse chronicling pandemic-era Astoria. I’ve attended several of Poets of Queens’s readings at QED Astoria. (During the pandemic, I had to go local, and when I went local, I went deep.)

At one of the readings this year, I heard poetry read by Maria Lisella, the poet laureate of Queens.

Didn’t know that Queens has a poet laureate? It does. So does the Bronx (Haydil Henriquez), Brooklyn (Tina Chang), and Staten Island (Marguerite Maria Rivas). I couldn’t find a poet laureate for Manhattan, although New York State has one in Patricia Spears Jones.

What I learned today is that Maria Lisella would like to step down from her role as poet laureate of Queens. The same weekend that I travelled to Governor’s Island, Lisella wrote a letter to the Queens Gazette, pointing out that the installation of her replacement in the role is long overdue. “Traditionally,” she wrote, “Queens Poet Laureate candidates were interviewed and judged by a team of local poets, representatives from Queens’ cultural organizations, colleges such as: St. John’s University, Queens College, as well as the Queens Council on the Arts, Queens Museum, Queens Theater, thus creating a broad base of contacts for the incoming Queens Poet Laureate.”

Her letter ended with a call to action that others write to Queens Gazette to encourage the Borough President to act upon this next appointment. This call was answered by Bruce Whitacre, a fun and generous poet with a new book out, by KC Trommer, founder of Queensbound, “ a collaborative audio project founded in 2018 that seeks to connect writers across the borough, showcase and develop a literature of Queens, and reflect the borough back to itself,” by poet and librarian Micah Zevin and by Dr. Tammy Nuzzo-Morgan, poet laureate of Suffolk County.

Apparently, letters to the editor at the Queens Gazette are addressed to QGazette@AOL.com.

In case you’d like to join the ranks.

Pentimento, Palimpsest, can I have a word?

“Palimpsest” (according to the American Heritage dictionary I received for Christmas when I was 12 years old) means the following:

“A written document, typically on vellum or parchment, that has been written upon several times, often with remnants of earlier, imperfectly erased writing still visible, remnants of this kind being a major source for the recovery of lost literary works of classical antiquity.”

The same dictionary has no definition for “pentimento”, so I went to the internet, which told me it is defined as “the presence or emergence of earlier images, forms, or strokes that have been changed and painted over.”

Both words sort of mean the intrusion of an earlier work into the current one. Sort of. But is there a similar word for theater?

I have reflected on this recently as I have watched two performances of Shakespeare – the Ralph Fiennes/Indira Varma production of MACBETH in Washington, D.C. last month, and a performance of TWELFTH NIGHT by the Axis Theater Company earlier this weekend. I’ve wondered if there was a word for the theatrical déjà vu one experiences during a new production of a play you have seen numerous times before. I went to TWELFTH NIGHT knowing I had seen the play several times, most notably the “star-studded” production at Shakespeare in the Park (Michelle Pfeiffer, Jeff Goldblum, Gregory Hines, John Amos) decades ago, but, as often happens now, during the performance, glimpses of other productions emerged from my memory.

There was a production where all the characters were dressed in swinging 60’s attire, and the “hey nonny nonny” had a British Invasion feel; another one at one of those mildewy Village theaters – maybe the Pearl Rep? — which long ago lost its lease but which featured a particularly fine “make me a willow cabin at your gate” speech by an actress I’ve otherwise entirely forgotten.

So is there a word for this?

And never mind MACBETH. Save one prominent Lincoln Center production which I did not complete, most of the productions of MACBETH I’ve seen have been cobbled-together second-floor or church basement productions, all overshadowed by the first MACBETH I ever saw. I saw it six times because I was working at my first job in the outside world, as an usher in the local repertory theater when I was fifteen years old. We were also reading MACBETH in my Shakespeare: Tragedy class (yes, there was also Shakespeare: Comedy) and MacBeth himself was kind enough to visit our class and tell us that the curse of the Scottish Play was real, that there had been a fire at the theater that had destroyed all the costumes.

MACBETH is a good play for high school; it has themes and witches and birds, a tragic flaw and an inevitability. And it is short – too short, some say. Earlier this spring, I saw MACBETH: AN UNDOING at Theater for a New Audience, which presents (sort of) MACBETH from Lady M’s point of view, gender-flips the madness and produces so much blood (and I was sitting so close) that I could at one point hear it dripping from a slain character onto the stage floor.

At the talkback afterwards, the playwright and the Lady M floated out the concept that the MACBETH we know is a heavily edited one. So much occurs offstage. Lady M scolds MacBeth “had I so sworn as you have” when we have never seen him swear to anything.

In the production I saw in D.C., Ralph Fiennes was excellent, as excellent as Kenneth Branagh when I saw him in HAMLET in Stratford-upon-Avon. I am floating out MY theory that these two, roughly contemporaries, were raised on Monty Python and FAWLTY TOWERS and found a weird, cruel humor in their dark stories that made their characters seem strangely familiar.

HAMLET, now. It is for that play that I need the word – the word like palimpsest or pentimento. I have seen so many productions of it that I can only reproach myself for not keeping better records. My obsession with HAMLET is a subject for another time. But in the meantime, I would like a word.

Basic Grandeur

In 2023, my New Year’s resolution was to take my lifelong flirtation with poetry, which I have written about elsewhere, into the next step. I needed to take a poetry writing class. I must have found my first class on Facebook. It was run by a nice woman who used to run a writing group in St. Louis, and much of the group were her St. Louis former cohorts. The class got me over the first hurdle, which was to write poems and share them with strangers. But it was too easy, so my next class was with the 92nd St. Y with an instructor who I won’t name because I found both her and her approach very chilly.

By now I was Goldilocks – too easy, too hard – so I submitted a few poems again to the 92nd St Y, to Advanced Poetry with Maya C. Popa because I wanted to work with her. I never expected to be accepted. But I was. And she was just right. I typed “write” the first time – Freudian, perhaps, but not a slip.

Then I went to podcasts. The Slowdown is a podcast hosted currently by Major Jackson, formerly by Ada Limon, which begins with a rumination from the host on anything going on in his/her/their life, followed by a poem. These podcasts are pleasant, but I need to hear a poem more than once. Which is what happens on Poetry Unbound, hosted by Padraig O Tuama, who reads the poem, reflects on it at length, and then reads it again. The New Yorker Poetry podcast hosted by Kevin Young is also on heavy rotation in my podcast feed. (Do people still say “heavy rotation”?)

Back to classes: I’ve had several more with Maya C. Popa, but I am a flawed student. I am conflicted about sharing my poetic work (“work”!), I don’t know how to revise, I don’t know some of the terminology my classmates are throwing around , sometimes I freak out and bail, and this is a run-on sentence. But now I’m hooked.

Many years ago, for April is Poetry Month, I posted a fragment of a poem, along with the title and name of the poet, on my Facebook page. I decided this year to do this again, with the proviso that I only highlight work by living poets. (Someone forgot to tell me that Eavon Boland had died.)

I front-loaded this endeavor by stockpiling two weeks’ worth of snippets of poems. I started with poets I “knew,” in the sense that I had met them at a writer’s conference, or heard them read, or generally been in a place where for a pulse of a moment (poetic?), we breathed the same air. So this included Patricia Smith, Kathleen Graber, A. Van Jordan and Jon Riccio, all of whom I encountered at Vermont College of Fine Arts. They were followed by Poets of Queens – Jared Harel, Jared Beloff and Oleana Jennings. And then people I’d encountered in magazines, or whose books I’d purchased.

The selection of the day was not dictated by any circumstances of the day. For example, in the past , I have chosen a poem reflecting my sister’s interests on for her April birthday. And many worthy poems were not included simply because I could not find an engaging snippet that could be easily extracted from the larger work.

As they say in baseball (also an April event), there’s always next year.

The Parks Department Removed the Errant Trees

This morning, as I set the breakfast eggs to boil, I heard the chatter of men outside my kitchen window. My kitchen window faces on to the stem of the “H” of the building in which I live, a kind of courtyard-cum-shrubbery landscape lovingly tended by my neighbor Rose and the various women she gently persuades into to help her, a group I call the “gardening brigade,” a group to whom I do not add my skills, but I have none in that regard.

These men were no friends of Rose’s. They shuffled against the cold with the air of aimless purpose of men brought together to do A JOB. In this case, the JOB was to undo a rather stupid earlier job, namely, to remove a series of four trees planted in the middle of the sidewalk on 29th Street.

You may have read about these trees here or here or here.

I saw them last Thursday, when I ventured out to the drug store upon feeling the swelling of my glands. I knew a cold was coming on and I wanted to get provisioned before I was confined by it. I stopped to take a photo of this sapling planted in the middle of the concrete sidewalk, a location of doom, and then set off to get medication, thinking no more of it until I ran into my neighbor Hannah, who asked me about the trees. I knew nothing more about the trees than any other hapless resident but pointed out that in a few years when the trees grew (if they were permitted to grow), their roots would begin to disrupt the sidewalk, as has already happened on 31st Avenue, in particular the sidewalks abutting the Trinity Lutheran Church.

Then I went home to sniffle into the New Year.

From my laptop on my couch, I typed out my year in reading list for 2023. It struck me as scant. There were many, many books I did not finish last year. I did not finish several poetry books — a few by friends — because it takes me forever to read a book of poetry. I managed the two by Ada Limon only because I was in a wonderful class held by Soapstone where I was easily the least poetry-literate and had to cram to keep up.

I don’t see how a book of poetry can be a page-turner. I’ve never understood the Sealey Challenge — a book of poetry a day for an entire month. A single poem a day would be a lot for me. I am a very slow reader of a poem, and books taken even longer, because I need to think about how the poems are in conversation with one another. Or maybe I am still a novice. Or maybe there is no maybe about that.

Other reasons I did not finish — I was reading the book for research and did not need to know all the particulars of, say, the life of John Winthrop, or the entire history of the coffee industry. Or at least I could skim it, for my purposes. And sometimes I didn’t finish a book because the book did not compel me to finish. There are more books out there awaiting attention.

So without further ado — the list for 2023. Italics means I reviewed it somewhere, and bold means it was a favorite.

Nonfiction

Crying in H Mart – Michelle Zauner

What Are You Looking At – Will Gompertz

Jersey Breaks – Robert Pinsky

Cary Grant’s Suit – Todd McEwen

Invisible Cities – Italo Calvino

Voice First – Sonya Huber

Love and Industry – Sonya Huber

How to Kill a City – Peter Moskowitz

Women We Buried, Women We Burned – Rachel Louise Snyder

Old in Art School – Nell Painter

The Third Rainbow Girl – Emma Copley Eisenberg

The Slip – Prudence Peiffer

Fires in the Dark – Kay Redfield Jamison

Is There God After Prince – Peter Coviello

The Red Parts – Maggie Nelson

St. Marks is Dead – Ada Calhoun

Fiction

The Girls in Queens – Christina Kandic Torres

Babel – R.F. Kuang

Roses, in the Mouth of a Lion – Bushra Rehman

The Cloisters – Katy Hays

Boundless as the Sky – Dawn Raffel

Forbidden Notebook – Alba de Cespedes

The Only Woman in the Room – Marie Benedict

Take What You Need – Indra Novey

Yellowface – R.F. Kuang

Anatomy of a Blackbird – Claire McMillan

All Among the Barley – Melissa Harrison

Normal Rules Don’t Apply – Kate Atkinson

I Have Some Questions for You – Rebecca Makkai

One Woman Show – Christine Coulson

Now is Not the Time to Panic – Kevin Wilson

The Wren, The Wren – Anne Enright

Mysteries

A Time to Kill – Anthony Horowitz

The Twelfth Night Murder – Anne Rutherford

The Bandit Queens – Parini Shraff

The Locked Room – Elly Griffiths

The Stranger Diaries — Elly Griffiths

Poetry

The Gospel According to Wild Indigo – Cyril Cassells

The Hurting Kind – Ada Limon

The Carrying – Ada Limon

I hope when I repeat this post in 2024 that I will report that I have read more entire books of poetry, cleared some of my research shelf, and banged out a draft of dog cafe. Until then, maybe all your trees remain where you plant them!

Kicking and Giving

I have now completed the second week of my fully-remote life. My previous job had a one-day-a-week-in-the-office policy for those of us in IT. For some reason, although I was in the research library, I was umbrellaed under IT. (My inability to master layout in the upgraded version of WordPress tells you allyou need to know about me working in an IT department.) When I asked my boss why the library was IT, his reply was “Gotta put us somewhere,” which effectively sums up what led me to leave that job — the lack of engagement, the listless dismissal of legitimate inquiry. The loneliness. In my new role, I am back to research umbrellaed under business development, which sets the world right again, but it is fully remote. Although this is only the difference of one day a week, it is a mindset which sets the mind reeling. To ward off the loneliness, I have committed myself to Pilates and knitting, two things at which I will be terrible for the foreseeable future, but both of which are within walking distance (there are two knitting groups that meet at different bars. I know one stitch.)

And then daily, I take long walks and write in a coffee shop. There is Chateau le Woof, of course, but nearer to home, so that I can get a walk-and-write in before logging on to work, there are three cafes: Under Pressure, Madame Sou Sou and Astoria Coffee. Under Pressure has a high-tech, sleek European vibe, a business-district-transformed-from-its-industrial-past-near-a-branch-of-the-Guggenheim-and-a-W-hotel kind of Europe. Madame Sou Sou has an Old Town European vibe, a cafe-on-a-narrow-street-full-of-quaint-shops-that-are-always-closed-recommended-by-the-landlady-at-your-AirBnB kind of Europe. Astoria Coffee has no European vibe at all. Extremely small even by NYC standards, it is resolutely Astorian, patriotically displaying on its limited wall space art photos of Astoria taken by local photographers.

But it is at Under Pressure where I set my first scene.

Despite its only-in-town-for-fashion-week interior, its clientele is mainly Greek and mainly working class. There is outdoor seating where you can watch the elevated train go by, or watch people line up to order gyros from the Greek on the Street food cart, or watch a traffic cop strolling down the avenue looking for victims. Under Pressure’s employees are Greek,and if their highly amused reactions at my attempts to greet them in their native tongue are any indication, no amount of living in Astoria will help my accent. I was sitting outside with my coffee and my notebook, earbuds in but podcast off. Three men were seated behind me, Queens natives by their accent, contractors by their conversation.

Guy on phone: “Look, I told you I needed you to have the bathroom done by the end of the week . . . that ain’t my problem. . . do what you gotta do. Come in early, stay late, get it done.”

I returned my focus to my to-do list, writing a list of what needed to be written, which is about all the writing I’ve done during the job transition. I heard a voice say “She’s not friendly,” and a moment later a man walked by, his Shiba Inu on a leash trotting alongside him.

Warning: the language below is foul but accurately recorded.

The first man said, “What the fuck! Not friendly!”

The second man said, “The fuck bring it out in public for if it’s not friendly.”

The third man said, “I’ll kick that fucking dog.”

At this point, I pulled out my earbuds and turned around.

The first man at least looked abashed. “Didn’t think you could hear with those things in.”

I explained that the Shiba Inu is a loyal-owner breed, until a few exchanges compelled me to stop. The second man muttered “Shiba Inu,” like it was a new obscenity to welcome into his lexicon. The dog kicker said “I got a pit bull. He don’t like people, I don’t take him outside.”

I held up my palm in the universarl signal for “I will now exit this conversation” that in this case meant “I have no wish to play the extra in a community theater production of Goodfellas.”

Later in the week, I sat at Madame Sou Sou with my coffee and notebook writing about the Under Pressure encounter when I found myself within earshot of a coffee date, a young American man, a young European woman, awkward (“I like your shoes”) and endearing. He explained that he would spend the next day at a “Friendsgiving” and I happened to lift my head in time to see her tumble the phrase in her mind, extrapolating from her familiarity with “Thanksgiving” as a North American holiday to ask “What is a ‘giving’?” .

As he explained, I entertained the idea of a “giving,” a celebration where people gather out of choice, not obligation, not freighted with travel rushes and mandatory dishes, expectations, disappointments, grudges, too much stuffing, stuffing of everything.

So, my friends, I wish you a good giving. (But no kicking.)

Is there a place that means a lot to you?

Yesterday I conducted the second of my readings/workshop at Chateau le Woof. It was, New York-famously, the seventh consecutive Saturday of rain, so my expectations of attendance were low. Who would venture through more sogginess to attend a reading of a work-in-progress advertised by an admittedly cute but somewhat vague flyer?

Yet, people came. One was my friend Tess, who I met at the VCFA conference last August, her friend Hannah, two kind neighbors, and a woman who I met in the most interesting manner. This work-in-progress has been a work-in-progress, as I shift and distill its focus from so many tantalizing possibilities. Initially, I began visiting the Chateau le Woof (aka “the dog cafe”) just after the vaccines were rolling out, in the late spring of 2021. I was privileged enough to be able to work from home, but also stir-crazy enough to need to be somewhere other than my home, with other people, yet not indoors. The dog cafe, an indoor-outdoor space, was perfect. I reflected on how we had quarantined ourselves during this pandemic, but during previous epidemics, New York City had quarantined the sick on the islands surrounding Astoria — Roosevelt Island, previously known as Welfare Island and before that Blackwell’s Island, had been home to hospitals, jails, poorhouses and a notorious lunatic asylum. North Brother Island had been home to a tuberculosis hospital. Hart Island was a potter’s field begun after the Civil War and in active use during the height of the pandemic, where graves were dug for the unclaimed dead by the unhappy residents of Riker’s Island.

I still have a draft of that chapter — “Exiles of the Smaller Isles” — but realized I could not use the background research I’d done on Typhoid Mary. She was sentenced to life on North Brother Island, not in the tuberculosis hospital (where she worked as a lab assistant) but in her own small cottage from which, in the imagination of novelist Mary Beth Keane in her novel FEVER, Mary falls asleep to the sound of the rushing currents of the Hellgate, a rapid, still-dangerous stretch of the East River between Ward Island and Astoria. FEVER is an excellent if bleak novel detailing the options of an unmarried immigrant woman at the end of the 19th century. At one point, the caretaker on North Brother Island points out to Mary that her life in her tiny cottage with her little dog, however lonely and powerless, is still much better than some have it.

My favorite of these books was TYPHOID MARY: AN URBAN HISTORICAL which was surprisingly hard to get a hold of, considering its author, Anthony Bourdain. It is top-of-the-game Bourdain, scathing and snappy, but I had to get it on Kindle, because it may be out of print. So it was not among the stack of books I took to the closest Little Free Library. I deposited them and at the same time was delighted to see that the small wooden box held a copy of UNCOMMON GROUNDS, a history of coffee, which was on my list of books I needed for research.

Another woman browsing the Little Free Library eagerly grabbed ALL the Typhoid Mary books, with such enthusiasm that I tilted my head at her. She explained that she was an epidemiologist with the New York City Department of Health.

“So . . . how was your pandemic?” I asked.

She attended the reading, along with her friend, another epidemiologist.

I started keeping this blog such a long time ago that I forget my own logline sometimes, which ends with “champion of the chance encounter.” This was one, if ever there was one.

Recent Comments